From Purple Heart To Persona Non Grata

A Hawai‘i Veteran’s Struggle to Fight Deportation

Immigration lawyer Danicole Ramos rides a wave off Laniakea Beach on O‘ahu’s North Shore. Photo courtesy of Valentin Feltrin

Riding 2- to 3-foot waves on Oʻahu’s North Shore this spring, Danicole Ramos was happy to be back in the surf after years spent studying and collecting degrees in Seattle and Washington, D.C.

Ramos, 31, who grew up in Waialua, had rushed to Hale‘iwa Ali‘i Beach Park after work on March 13, and was hoping to catch a few more waves as a sunset painted the skies brilliant shades of purple. Straddling his surfboard, he focused on an incoming swell when another surfer paddled over.

“He says to me, ‘I saw on social media you’re an immigration lawyer.’ He gets real chatty and says, ‘maybe you can help my friend,’ then tells me this crazy story about a Purple Heart veteran who was shot and now they want to deport him.”

“I was like, ‘What!?’ Why is he telling me this while I’m in the water? This is the weirdest referral I’ve ever gotten.”

Just two years after earning a law degree from the William S. Richardson School of Law at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Ramos didn’t realize he was about to ride the biggest wave of his life. The case quickly attracted local, national and even international attention.

The day after getting the referral, the newly minted lawyer and immigrant veterans advocate at the Refugee and Immigration Law Clinic in Honolulu contacted the veteran, Sae Joon Park. Although Park was born in South Korea, he had moved with his mother to the United States when he was seven and later, with a green card in hand, spent nearly a half-century in the country.

Piece by piece, Ramos, who is also a captain in the Hawai‘i Air National Guard, began investigating how a decorated veteran could find himself persona non grata in America.

Here are the facts that he collected: Park, a service member wounded in battle while serving in the U.S. infantry in Panama in 1989, is awarded a medal after being shot twice and nearly dying. Following treatment in the U.S., and suffering post-traumatic stress disorder, he self-medicates with street drugs and gets convicted in New York. He has to sacrifice his green card despite his exemplary service.

After serving 2 1/2 years in prison, Park pulls his life together, gets clean, holds a job back in Hawai‘i and pays taxes for more than a decade. Finally, with the election of Donald J. Trump and his administration’s crackdown on undocumented residents, Park is told at his annual check-in with the local Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) office to self-deport back to South Korea or be forcibly removed, a prospect with an uncertain destination or timeline.

Then the threat became immediate.

“When we checked in at the ICE office, the officer was about to cuff him right there,” Ramos recalled. “I couldn’t believe it. The officer said, ‘Because of this new regime’ — he literally used that word — ‘you’re going to get deported.’”

Ramos was stunned.

“Everything about Park is American except on paper,” he says.

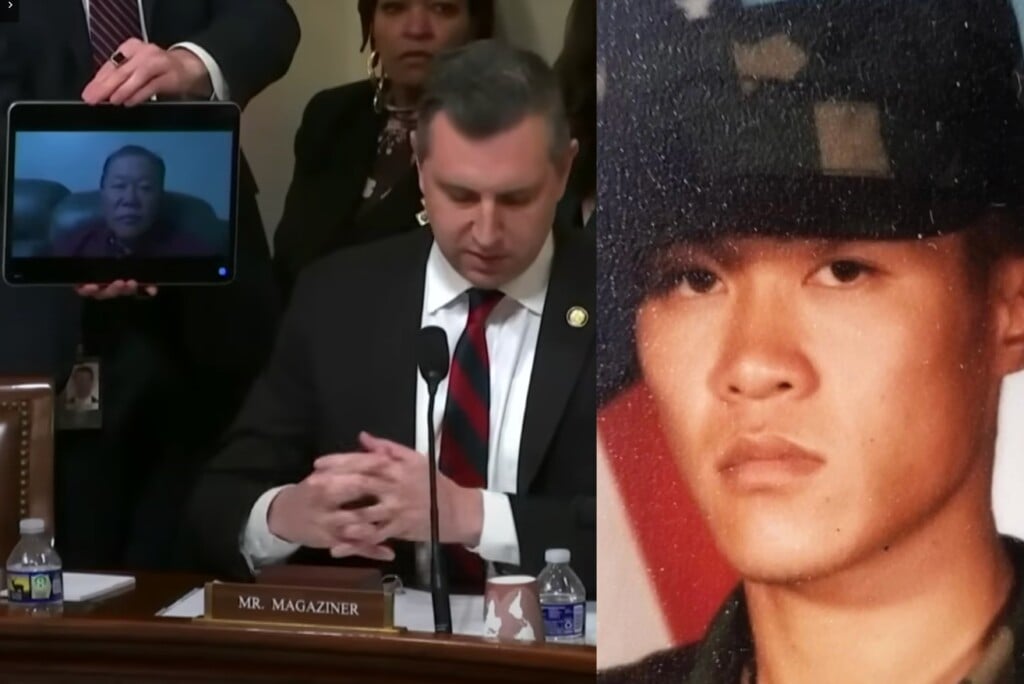

“I’d been doing annual check-ins for 14 years,” Park recalled during a video interview from South Korea with Hawaii Business Magazine. “But when we went in June, the officer started reaching for his handcuffs. He said, ‘Oh, you’re getting removed. We’ve got to remove you.’”

After appeals to the officer’s supervisor, they agreed on a compromise — they’d put an ankle bracelet on Park and give him three weeks to self-deport, according to their account.

“Thank God Danicole was with me because without him I would have been detained that day,” Park says. “I always feel blessed and always feel like there are angels looking over me. I really do.”

A spokesperson for the ICE office in Honolulu did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

With the threat of forcible deportation looming and seeing no other recourse, Park carried through on his decision to self-deport back to Seoul. At an emotional farewell at Daniel K. Inouye International Airport in Honolulu on June 23, he says he feared he’d never see his mother and her sisters again, and would miss important events in the lives of his grown son and daughter.

His only hope was for Ramos to convince an uncaring bureaucracy to consider his troubled past and weigh his subsequent years of being drug-free, holding a job and paying taxes, and his exemplary service to the country.

For his part, Ramos, having nearly exhausted every legal recourse in cases that had already been adjudicated, started spreading the word about Park. He created an online petition, seeking signatures in hopes of reopening Park’s case to “bring him home.”

So far, the site has garnered more than 8,700 signatures. Ramos hopes to convince the district attorney’s office in the Queens borough of New York, where Park was convicted, to revisit the case. If it could be changed to a misdemeanor, there’s a chance the deportation order could be removed.

There’s no indication the Queens district attorney has any interest in re-examining the case, Ramos said.

“It’s a long-shot,” he admits.

A spokesperson for Queens County District Attorney Melinda Katz did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Purple Heart veteran Sae Joon Park with his mother in Honolulu at a family gathering. Photo courtesy of Sae Joon Park

TOLD HIS MOM HE’S ON VACATION

Back in South Korea, the 55-year-old Park is trying to get reacquainted with distant relatives, many of whom he last saw 30 years ago. Although he can speak Korean, he struggles with the written language. And he’s troubled by a recurrence of PTSD, which was triggered by being forced to leave the land where he spent the last 48 years.

“It’s been really tough,” he says of the transition to a country he doesn’t really know. “Especially the first three or four days, I guess it was like PTSD. I’ve been overwhelmed, so every morning I would cry nonstop for two or three hours, just weeping.”

“I’ve been getting reacquainted with my relatives,” Park says. “They don’t really know my story. They just know I got deported. It kind of hurts.

“Of course, I made my mistakes,” Park acknowledges. “I told them I was going through PTSD, self-medicated. Korea is a very, very anti-drug country.…When it comes to drugs, it’s very shameful. So I had a hard time at first trying to explain to them. But more and more, they’re understanding what I’m going through.”

On the bright side, Park is able to spend time with his father, who lives in South Korea and recently turned 91. As for his mother back in Honolulu, Park says she suffers from dementia and doesn’t know that he likely won’t be coming back.

“We’ve told her that I’m on vacation,” Park says, and then turns quiet. “I try to comfort her as best I can.”

Sae Joon Park in military uniform after he returned to Los Angeles from basic training in the U.S. Army. Photo courtesy of Sae Joon Park

‘I FELT LIKE A LEGAL RESIDENT’

Park’s parents divorced when he was two, and at the age of seven, he was sent to the U.S. from South Korea to live with his mother. After a year in Miami, they moved to Los Angeles, where he grew up and went to high school. After graduating, he enlisted in the U.S. Army infantry.

Asked why he never converted his green card to become a naturalized citizen, Park paused and reflected, as though trying to explain why a race car driver doesn’t conserve on gas.

“The thing about that green card,” he says, is that “growing up all my life in the States, I felt like a legal resident. I never had any issue. I could travel. It never entered my mind that I had to hurry up and get citizenship.

“And you have to understand,” he continues. “I was a teenager and had a lot of stuff on my mind. My mind’s not focused on trying to get citizenship. I felt like I was an American. Then after I got shot, it was like, oh, that’s an automatic citizenship.”

After joining the military in 1989, Park was quickly sent to Panama where he was stationed. Three months after arriving, President George H.W. Bush ordered the invasion of Panama in “Operation Just Cause,” an effort “to protect the lives of Americans” living there and to capture General Manuel Noriega, who was later convicted on drug trafficking, racketeering and money laundering charges.

Park was one of 20,000 U.S. soldiers involved in the fighting. Twenty-three U.S. soldiers were killed in combat, and another 325 wounded.

Park recalls the day he was shot. “The second day while patrolling the housing area, I heard some gunfire in the backyard…I saw some enemies under a truck, and I started opening fire and hit some in the legs. And then I saw a couple more soldiers running across, so I turned to let my sergeant know. That’s when I got shot.

“I was conscious through the whole ordeal,” Park recalls. “It felt like a little pin in my spine. I realized I was on the ground, and my leg was all twisted up. I realized, oh my god, I’m shot in the back, so I start reaching for my leg and I had no feeling, and I thought, ‘oh, I must be paralyzed.’ And then I started thinking, ‘oh no, I’m not just paralyzed, I’m actually dying right now.’”

A medic pulled him out of danger and stabilized him so he could be medevacked to a military hospital in San Antonio, Texas.

Park had been hit by two bullets, one from an AK-47 and another from an M-16, which “zigzagged, dodging all my vital organs, the lung, liver, heart,” he recalls. One bullet pierced the dog tag he wore around his neck and left an imprint on his chest where the bullet pushed the metal into his skin. “Doctors called it a miracle” that he survived, he said.

While in a hospital bed in Texas, President Bush visited the wounded and thanked the soldiers for their valiant behavior. Later, Park says, a four-star general awarded him with a Purple Heart medal.

While he was in the military, “no one ever asked me about my citizenship status,” Park notes.

After being discharged, he says, the military’s benevolence ended.

“From the day I was shot until around 2008, I didn’t receive a penny of any kind of benefits from the military,” Park says. “The VA would turn me down when they looked at my back. ‘Oh, the bullet hole isn’t big enough. You’re fine, you can bend over. Zero disability.’”

And in 1989, the military did not treat his mental condition. Park said it wasn’t until 2007 or 2008 when the Veterans Administration reached out to him to evaluate his psychological wounds and finally treated his PTSD.

When he pled guilty the following year to drug possession and later skipped bail, triggering another felony, Park’s excuse of PTSD fell on deaf ears. He ended up serving more than two years at Mount McGregor Correctional Facility about 50 miles north of Albany, N.Y. “There were 600 inmates and one Asian — me,” Park says.

Stripped of his temporary residence status conferred by his green card, he was suddenly rendered deportable.

Although Park could have been sent home at any time, he was told his case wasn’t a high priority and he was allowed to carry on with his life as long as he kept clean and checked in with authorities every year, Ramos says.

He returned to Hawai‘i where he had first arrived in 1995. At that time, Park says, “although I was struggling with my addiction, I got married and had two beautiful children.” Six years later, he divorced and moved to New York, where his troubles later caught up with him.

Sae Joon Park in military fatigues during his service in Panama, 1989. Photo courtesy of Sae Joon Park

CITIZENSHIP AS RECRUITING BENEFIT

Even as the current administration has set daily quotas to remove undocumented residents across the country, the U.S. military actively enlists noncitizens for the armed forces, offering streamlined avenues for veterans and active service members to become citizens.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security website for U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services states that service members, veterans and their families may be eligible for “certain immigration benefits in recognition of their important sacrifices.” The provisions “reduce or eliminate certain general requirements for naturalization, including the requirements for the applicant to have resided in and been physically present in the United States for a specific period of time before naturalizing.”

The website touts its record: “Since 2002, we have naturalized more than 187,000 members of the U.S. military, both at home and abroad, involving citizens from more than 30 countries. From 2020-2024, more than 52,000 service members were naturalized, including a 34% increase in 2024 alone.”

Indeed, offering a path to citizenship is a potent recruiting tool, says Ramos, who described another of his clients who signed up at a recruiting station in the Philippines but was later denied citizenship. Ramos said that once recruits have enlisted and begun their service, many have struggled to get necessary information or assistance to begin the path to citizenship.

“Sae’s story is extreme and the worst of what happens, but it’s just a pattern of how the military treats veterans and service members. Citizenship is a draw for people, but it’s just not a priority once they’re in.”

“I have eight to 10 clients who are veterans seeking naturalization,” Ramos adds. “Three or four have very serious situations – veterans of Desert Storm and other wars and got into trouble or were injured and now some are bedridden. They weren’t naturalized but they need naturalization before they can get help.”

ONE BIG BREAK IN HAWAI‘I

Park’s story is one of redemption denied in a country struggling to accept a nuanced approach to immigration. The Trump administration’s aggressive campaign to remove anyone without proper documents ignores the fact that businesses have long relied on the essential work of noncitizens — in farms, factories and even the military.

After his New York convictions and return to Hawai‘i, Park turned his life around. But he had one big break when an employer took a chance on him.

Russell Wong, chief operating officer at Aloha Kia in Honolulu at the time, says probation officers often called to urge local employers to give jobs to ex-felons so they could gain an income and live at home rather than at half-way houses. The officers said the prospective employees were regularly drug tested and had periodic check-ins to make sure they didn’t relapse.

“They just needed a shot to get re-integrated back into society,” Wong recalls of the encounter more than a decade ago. One of the people on the list was Sae Joon Park.

“So I met with Sae — he’s a Purple Heart veteran and everything. It made sense from what I knew about him. In an interview, he talked about his life and showed integrity. I wanted to give him a chance. I didn’t think it was a big risk.”

But it wasn’t as simple as making a job offer. Auto dealership salespeople need to be licensed, unless the board waived the requirement. Park did not have a license.

Wong asked them to make an exception in Park’s case. “I wrote a letter saying I would stand by him and take responsibility for him. My impression was that he wanted redemption. He wanted to be a better person, and he was sincere. It was enough to convince me he was a risk worth taking.”

The board consented, and Park was hired, staying with the company for about a decade.

“I’d like to think I helped him out,” recalls Wong, who is now regional vice president for Aloha Kia. “He did a lot to bring sales for the company, too.”

The two haven’t talked in years. But during an interview from South Korea, Park’s eyes teared up as he recalled the man who had helped him when no one else would.

“When I got released, I couldn’t get a job,” Park recalls. “But Russell Wong wrote this wonderful letter saying he knew about my priors and was still willing to help me rebuild my life…. I really do owe him a lot.

“That motivated me to be a good father and do the right things and build a great life in Hawaiʻi — a life I’m so proud of.”

NO COUNTRY FOR IMMIGRANTS

The timing of Park’s latest annual check-in with ICE may have worked against him.

In late May, after the administration’s “border czar” Tom Homan announced his teams had arrested some 200,000 people in the first four months of the Trump term, some media reports noted that was a slower pace than under former President Joe Biden.

Not to be outdone, White House aide Stephen Miller, the architect of Trump’s immigration policy, upped the ante, directing ICE to triple its arrest quotas, to 3,000 per day. Officers ramped up their raids, broadening arrests far beyond the original stated target population of dangerous criminals.

Then, in a brief about-face after widespread protests over ICE roundups in the Los Angeles area, Trump acknowledged in early July that he was considering exceptions to the hardline crackdown to help farm and restaurant businesses keep loyal, yet undocumented, workers.

“We’re going to have a system of signing them up so they don’t have to go,” Trump told reporters during a trip to Florida. “They can be here legally, they can pay taxes and everything.”

But in a White House briefing later, spokeswoman Karoline Leavitt said there had been no final decision on the idea. While the president’s comments raised hopes among some in the business community who wanted to keep access to cheap labor, they sowed more confusion.

Shortly after Trump’s remarks, ICE officials resumed roundups in fields in California, Hawaiʻi and elsewhere. And in early July, U.S. Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins declared that farm workers would not receive “amnesty,” adding the administration wanted to rely on an entirely American workforce.

Miller’s hard line had prevailed.

Even so, the regimented crackdown, with a stated goal of removing millions of undocumented immigrants, has unnerved even some of Trump’s ardent MAGA base as news reports showed heavily armed and masked ICE agents forcibly rounding up men and women at their workplaces, on the streets and in their homes.

“Being in the military, it’s very conservative,” said Ramos. “After the news spread about Mr. Park’s case, I had veterans tell me, ‘I voted for Trump, but this is crazy. I never thought it would come to this.’ His story, regardless of party lines, is really disturbing. Hopefully it will educate people about how we treat veterans in this country.”

Indeed, Park’s case has struck a nerve across the political spectrum.

On the petition website, comments range from pity, to sadness, to outrage.

A 23-year Army and combat veteran wrote: “This is absolutely atrocious. He’s a decorated soldier, suffered wounds in combat, and the failed mental health system in the military at the time [led] him down a troubled path. He needs to be allowed back into the country that he served, and needs to be treated properly at the VA and with military resources for the psychological and physical wounds he sustained in combat. We help our veterans in this country, we don’t deport them!”

Another comment, from a person identified only as Ron, said, “Mr. Sae Joon Park bled for this country.…Yes, he made mistakes — over 15 years ago. But we don’t erase a veteran’s sacrifice over a decades-old rap sheet — we weigh the whole man. Queens County and the U.S. owe him more than a cold shoulder. They owe him citizenship.”

And a video comment showed a woman named Sara raising a crisp salute to Mr. Park, saying he had done more for the country “than most Americans would ever, could ever, and would want to ever, and you still believe in being a veteran, a supporter, and I praise you. Hats off to you, sir. Please, come home. You deserve it.”

Ramos’s petition asks the Queens district attorney — who was not in office when Park’s case came to trial — to drop the convictions for drug possession and bail jumping. “These convictions, as they stand, hinder his immigration attorneys from making the necessary motions in immigration court to cancel his deportation case and allow him to return to the United States.

“Past mistakes should not overshadow Mr. Park’s life of dedicated service,” the petition continues. “Compassion and justice demand that we reconsider his situation. Our national ethos and the values Mr. Park defended require us to act justly and with humanity.”

Danicole Ramos, immigrant veterans advocate at the Refugee and Immigration Law Clinic at the University of Hawaii-Mānoa law school. Photo courtesy of Danicole Ramos

THEY DON’T TEACH THIS IN LAW SCHOOL

Amid the swirl of legal and media demands on his time, Ramos sometimes pauses to consider how quickly his life has changed since that day in March while surfing on O‘ahu’s North Shore.

“This case has affected me a lot,” he admits. “I only passed the bar exam last year. And they don’t teach any of this in law school — about media and being in the public eye,” he said after appearing with Park in an interview on CNN.

But his passion for social justice, immigration and helping veterans runs deep. After finishing a business degree at Seattle University, he turned his attention to public policy while earning an M.P.A. degree at American University in the nation’s capital. While there, he worked as an administrative coordinator for United We Dream, America’s largest immigrant, youth-led network.

He said he remembers paying bail money out of his own pocket to get some of the kids out of jail so they could work together on their cases. That’s when he decided he wanted to become an immigration lawyer, and he returned to Hawaiʻi to apply to law school.

But before enrolling at UH, he worked as a policy analyst and lobbyist for Elemental Impact, a nonprofit investor in climate technologies.

One of Ramos’s former colleagues at Elemental and a surfing buddy, Benny Kim, said of Ramos: “He’s an empathetic and kind person and was always dedicated to helping people around him.”

“When we worked on climate issues together, he was always looking at a bigger picture, talking about immigration and refugee rights,” added Kim, who now works in New York for another organization.

During law school, Ramos served as a summer law clerk and extern for The Legal Clinic and represented an asylum seeker in Immigration Court. He was also a legal extern for Honolulu City Councilmember Matt Weyer and as a legislative aide to State Representative Sean Quinlan.

“I learned a lot about how Bishop Street worked,” he said, referring to the Honolulu street where many law firms and lobbyists are located.

Now he’s able to tap some of the skills of persuasion that he picked up from the experts who tutored him.

As an attorney at the Refugee and Immigration Law Clinic, attached to the UH law school, Ramos represents a range of clients seeking help applying for green cards, or veterans seeking naturalization or health benefits.

“It’s like a firm,” Ramos said of the clinic, which employs four attorneys and also gives law school students exposure to actual cases.

The clinic’s website emphasizes the important role of foreign-born residents in Hawai‘i’s labor force, and notes the clinic was established “to ensure that Hawai‘i’s most vulnerable immigrants would have access to legal services.”

“Over a third of healthcare support workers are immigrants, as are nearly two-fifths of the state’s farmers, fishers, and foresters,” according to the website. “Immigrants own over a quarter of businesses in Hawai‘i. As neighbors, business owners, taxpayers, and workers, immigrants are an integral part of Hawai‘i’s diverse and thriving communities.”

‘I EARNED THAT LIFE’

Back in South Korea, Park reminisces about once being part of Hawai‘i’s immigrant community and making a contribution.

“I earned that life,” he says. “I got to the point where I said, oh my god, I have a great life. I can live out the rest of my days just like this and be so happy. Both of my children turned out great…I really felt I earned all of that. I did a great job. I was proud of myself for the first time.”

To cheer himself up, he takes comfort by reading through thousands of notes from supporters and shields himself from the inevitable few who say he deserves what he got.

“I don’t have to defend myself. There are so many people speaking out for me, defending me. When I see that, I just break down and cry because I’m so grateful.”

One bright spot keeps Park going. Even though he has bouts of PTSD, as a veteran, he said he can go to a U.S. military base in South Korea to see a doctor for help with his disorder. He hasn’t set up an appointment yet, but hopes they’ll let him in.

“I was very proud of myself,” Park recalls of being a decorated U.S. soldier. “I have always been proud of my Purple Heart,” he adds, suddenly trembling with emotion. “It’s on my license plate, ‘combat wounded’ with a Purple Heart…I could even brag about what I did for this country. And yes, it’s been a big part of my life. I wouldn’t change anything. That’s a big part of who I am today.

“A hundred percent, I feel like an American.”