Kaua‘i Pediatrician Who Warned About One Toxic Pesticide Sees a Bigger Threat

Hawai‘i led the nation in outlawing chlorpyrifos, but Dr. Lee Evslin says pending legislation in the U.S. Congress might prevent EPA review of new scientific evidence, which opponents say could limit states’ roles in the future

This article was updated on September 2, 2025.

Hawai‘i isn’t often at the forefront of national policymaking, but its 2018 ban on a widely used but controversial pesticide set the stage for other states, the federal government and even the European Union to follow suit.

With much fanfare, then-Gov. David Ige signed the bill into law in June of that year after a heated public debate in Kaua‘i. Residents there had raised alarms about seed companies spraying the pesticide chlorpyrifos on fields near schools.

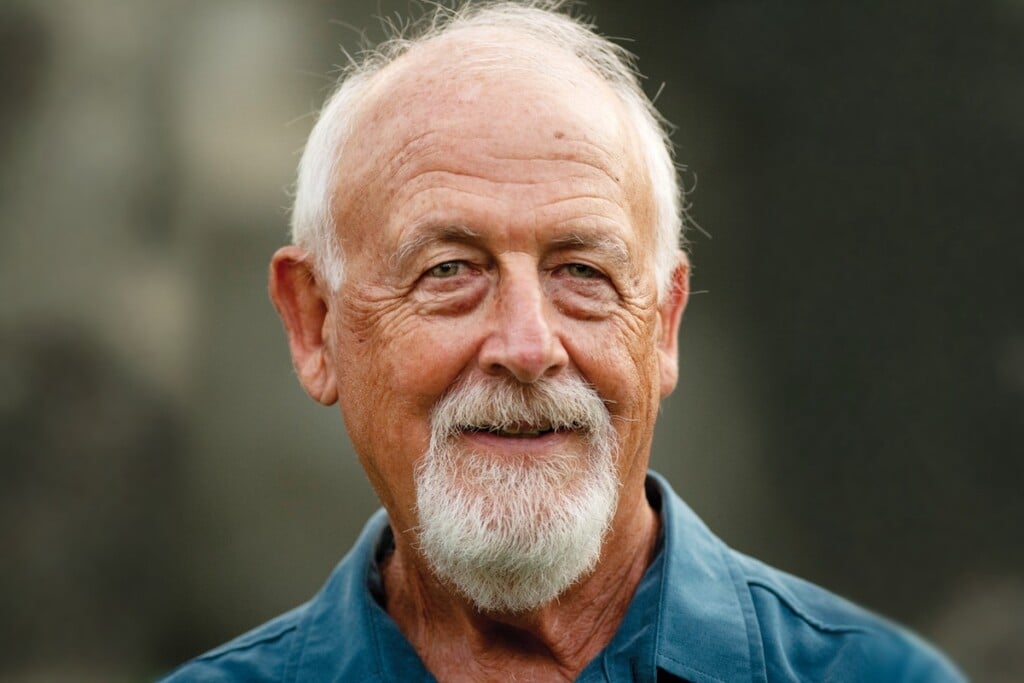

Now, a soft-spoken Kaua‘i pediatrician who helped focus state lawmakers’ attention on the health risks of chlorpyrifos back then is again sounding the alarm.

This time, the showdown is over a seemingly innocuous 71-word section of the appropriations bill that the U.S. House of Representatives will take up this month following their summer break.

“It’s a sleeper poison-pill,” says Dr. Lee Evslin, describing the provision that opponents argue could prevent Hawai‘i and other states from again setting their own pesticides restrictions.

“Hawai‘i’s children and families live closer to pesticide spray zones than most Americans,” Evslin wrote in an appeal to the state’s congressional delegation. He urged them to scrutinize the measure, warning that it “would lock in outdated federal determinations, preventing timely updates that could save lives and protect vulnerable populations.”

Opponents of the provision say it would also shield chemical companies from lawsuits by people harmed by pesticide use and would limit research that might document hazards posed by chemicals already on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s approved list, such as glyphosate, the prime ingredient in Roundup and other herbicides.

“It’s so much under the radar,” Evslin says of the section of the bill, which has been overshadowed in Washington by higher-profile debates involving tariffs, tax cuts, immigration enforcement and Jeffrey Epstein files.

“Tilting at Windmills”

With lawmakers returning to Washington, one of the first orders of business will be to debate and vote on the appropriations bill. From his island outpost in one of the western-most reaches of the country, Evslin is hoping his single voice can add to a roar that is heard in Washington.

He has sent letters to Hawai‘i’s congressional delegation, written articles and talked with those in his profession, hoping to convince anyone who will listen.

“It’s huge, how [the health risks] can be so well documented, and there’s so little publicity out there,” he says.

U.S. Representative Jill Tokuda, who represents the Neighbor Islands and much of rural and suburban O‘ahu, strongly opposed the measure. “This provision is a blatant giveaway to powerful pesticide manufacturers, shielding them from accountability while leaving families, farmers, and workers to bear the harmful consequences of toxic exposure,” says Tokuda, a Democrat, ahead of the vote.

But the math is against Democrats in the House, where Republicans outnumber them.

Evslin, who seems more at ease combing through academic journals or giving measured medical advice to a patient, muses at how he keeps getting pulled into the political arena despite his natural tendency to shy away from the limelight.

“To some degree I feel like Don Quixote, tilting at windmills,” Evslin says with a chuckle. “There’s a part of me that’s unbelievably passionate about it, and there’s a part of me that looks at myself from a distance.

“It’s a battle that I think is vital, and I understand that it’s daunting, and I tell myself, just do your best, take one step forward at a time.”

Evslin’s work to raise public awareness caps a career that included roles as CEO of Kaua‘i Medical Clinic and later Wilcox Hospital, Senior VP at Hawai‘i Pacific Health as well as private practices as a general pediatrician and sports medicine/wellness clinic physician.

He has drafted testimony for the American Academy of Pediatrics, has written columns for local newspapers and was a keynote speaker at the 2022 U.N. General Assembly Science Summit.

Evslin says he tried to pull away from medicine during a stint as a small-scale farmer on the Garden Isle after he retired, but science kept pulling him back. He says he was drawn to an increasing number of studies that showed medical hazards from chronic exposure to chemicals that are used in Hawai‘i at much-higher levels than on the mainland.

That’s when he bumped into less familiar territory of politics, where even the immutable laws of science are often treated merely as cards that can be traded in fungible transactions for personal, professional or partisan gain.

“At times I say to myself, ‘Am I nuts? I’m happily retired and have nine grandchildren. Why am I even doing this?’ But it feels so right to me, and I’ve become moderately knowledgeable. I feel that I should speak out.”

Evslin says he was at first a reluctant traveler in the campaign to ban or restrict certain uses of pesticides. He didn’t focus on pesticides – a catch-all category that also includes herbicides, insecticides and fungicides – until reading two papers in 2012 by the American Academy of Pediatrics, which reported on the health threats of chronic low-level exposure to pesticides.

“I’ve always been interested in why some people are healthy and some are not,” Evslin explains. “That’s been a thread of my career and looking at what you can do about it.”

“So, when these papers came out, that was a game-changer to a certain degree to pediatric thinking.” Up to that point, he says, pediatricians were taught to treat acute poisoning – accidental spray exposure or consuming a pesticide.

“If someone called me and said they took something, the first thing I would do is call the poison control center because they had the data at their fingertips” and could most quickly treat the immediate symptoms.

He adds: “The idea of chronic, low-level exposure to pesticides being dangerous just hadn’t been something I or most pediatricians thought about.”

That was about to change.

Three Growing Seasons a Year

Hawai‘i has played a critical role in the development of crop seeds that are sold by major companies around the world and become, literally, the source of much of the food consumed on the planet. That’s because those multinational seed companies – through complicated genetic engineering and hybrid techniques – need to test their creations before receiving regulatory approval. Currently, that means they need to show the seeds have performed through three growing seasons.

Because of its geographic location and benevolent climate, Hawai‘i is one of the few places in the United States that offers seed growers such favorable conditions. Companies such as Syngenta, Dow AgroSciences, DuPont Pioneer and BASF Plant Science were drawn to the ideal farmland on Kaua‘i to develop new seed strains, while Monsanto, now owned by Bayer, concentrates its farming operations on other islands.

In 2012, the companies operating in Kaua‘i “were reportedly spraying or applying 18 tons of restricted use pesticides in a relatively small footprint,” says Evslin. “It became a huge issue with activists on Kaua‘i.”

Evslin says the seed companies explained they had to use large amounts of pesticide because insects in the tropics were worse than on the mainland.

“So, if you compare our usage of chlorpyrifos, which is a very toxic insecticide, with the usage on the mainland, we ended up using about three times” mainland amounts, he says.

Shortly after Evslin had shifted his focus to chronic, low-level pesticide exposure, members of the Kaua‘i County Council introduced legislation to limit the use of chemicals in the fertile fields of the island’s west side.

“I wrote testimony for the hearing,” Evslin says. “At that point in my career, I was in my practice on Kaua‘i, which had a lot to do with wellness, so it was in my alley.”

About 15 other physicians and medical practitioners on the island signed the testimony he read to the hearing, which was packed with hundreds of people representing both sides.

Not comfortable in front of big crowds, much less emotionally charged ones like this, Evslin remained clinical, explaining that from a scientific perspective, it was important to think about the health risks from long-term, low-level exposure to the chemicals that were being sprayed in the community’s fields.

“All they were asking for was that they wanted no-spray zones around schools, they wanted stronger right-to-know language so that people would be informed about what was being sprayed where,” Evslin recalls.

Long story short: The council approved restrictions, the seed companies won a legal appeal that said only the state could impose such limits, and the state Legislature later followed up with its own law imposing a phased-in ban on chlorpyrifos on state agricultural lands.

Other states followed suit. Federal government attempts to bar the use of the pesticide followed a similar on-again, off-again pattern as the issue – and control of the EPA –bounced between shifting political camps and agendas.

Today, long after the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit vacated the EPA’s effective ban on chlorpyrifos, use of the pesticide still faces restrictions but is not banned at the federal level.

New Evidence of Harm Emerges

Coincidentally, a study published this month in the journal JAMA Neurology links prenatal exposure to the insecticide with enduring widespread molecular, cellular and metabolic effects in the brain.

Researchers for the study, from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles, and the Keck School of Medicine at USC, also linked the chemical exposure to poorer fine-motor control among youth.

“A study like this is a powerful argument for the ban that Hawai‘i enacted in 2018,” says Evslin, who had served on a state-county joint fact-finding task force on this issue, and it provides evidence about “the danger of the federal government saying that even a blockbuster study like this could not even be analyzed [under the pending legislation] until the next formal review of the chemical,” a process that occurs about once every 15 years.

That’s why he says Section 453 in the appropriations bill is so potentially dangerous.

“What they’re saying is that if new data comes along, they can’t spend money reviewing it to see if they should modify” existing rules, Evslin says. “So theoretically what that would mean is only every 15 years could you do research and point out issues and make a difference about the danger of one of these chemicals.”

Section 453 as Political Strategy

Environmental and other non-governmental organizations advocating for restrictions on certain pesticide uses have ramped up efforts to block section 453, which opponents say plays into the strategy of chemical companies.

After losing heavily in recent court cases, companies like Bayer/Monsanto have sought relief from state legislatures and courts, with limited success, according to Jay Feldman, executive director of one such group, Beyond Pesticides. Next, they turned to Congress.

“They do it in a very circuitous route,” he said. “They do it through an appropriations bill, where they basically say to EPA, ‘you can’t change the label [on pesticides] unless you do an extensive health assessment,” which can take over a decade. “So, they’re not directly saying you can’t sue manufacturers, they’re saying the EPA cannot allow a change in a label without these tremendous hurdles that are very time-consuming.

“The manufacturer then goes to the court, and says ‘Judge, we couldn’t change this label [to provide better warnings to consumers], because this is the label EPA gave us and Congress has precluded the change in label, so we can’t be held responsible for failure to warn.”

The sort of Catch-22 routine blocks the last avenue for litigants seeking relief for damages, he said. The irony, Feldman adds, is that the pesticide companies are the ones who helped write the language in the bills. “Whether that would even hold up in court, it remains to be seen, but it’s been done before,” he said.

In a statement, Bayer responded: “We agree that no company should have blanket immunity and, to be clear, the language in section 453 of the appropriations bill for the Department of the Interior would not prevent anyone from suing pesticide manufacturers. Anything to assert otherwise is a distortion of reality.

“As part of our multi-pronged approach, we support federal legislation alongside more than 360 agricultural organizations because the future of American farming depends on reliable science-based regulation of important crop protection products – determined safe for use by the EPA. Other measures include the support of legislation at the state level and a Supreme Court petition.

“Legislation at a federal level is needed to ensure that states and courts do not take a position or action regarding product labels at odds with congressional intent, federal law and established scientific research and federal authority….”

In court filings, Bayer unit Monsanto has argued that because the EPA has approved glyphosate-based product labels without cancer warnings, plaintiffs cannot sue under state laws for failure to include such warnings.

Even so, with the application of Roundup on farm fields around the country, lawsuits alleging health damage from exposure to the chemical also began piling up. After initially winning some of the lawsuits by claiming research showed the chemical was safe, Bayer started losing, big-time, and the losses and legal costs piled up.

As of August 2025, Bayer had settled about 100,000 Roundup lawsuits for about $11 billion, but another 61,000 cases remain active.

In a statement on glyphosate, Bayer said it “stands behind the safety of our glyphosate-based products which have been tested extensively, approved by regulators and used around the globe for 50 years. The EPA has an extremely rigorous review process which spans multiple years, considers thousands of studies and involves many independent risk assessment experts at the EPA.”

Political Twilight Zone

After the Kaua‘i hearings, the fact-finding recommendations and the County Council vote to restrict pesticide use around schools, Evslin says, he was stung by the seed industry representatives’ comments that he was “fear-mongering” and “unscientific” – the antithesis of his self-image.

“And that’s when I was struck by this kind of Twilight Zone. It was as if they weren’t looking at the same scientific information at all.”

A representative of the Hawaii Crop Improvement Association, which represents the seed companies, did not respond to Evslin’s assertion but in a statement said it supports the House measure.

The section, it said, will “help ensure that our hard-working agricultural producers across the country can rely on consistent agricultural labeling based on well-established and thorough scientific protocols.”

Peter Adler, a conflict resolution consultant and chair of the joint task force charged with finding common ground among the feuding sides, recalls the role played by Evslin.

“He did a lot of careful rounding up of studies,” Adler says of the task force debates. “It wasn’t just an opinion jamboree. It was much more based on trying to understand what the data was [concerning] the use of some of these pesticides.”

Adler says the task force sought to sort out which claims were real and which ones were exaggerated or imagined, what could be confirmed, and what couldn’t.

Evslin “was really good about pulling in a lot of data and groups of studies,” he says. “It was bringing evidence to the table. We’re not in a court of law, but we’re trying to work out [a solution in] a highly charged political environment. He was very fact-centered.”

Evslin’s concerns intensified when he later started digging into the scientific studies on glyphosate, the active pesticide ingredient in Roundup and many other herbicides.

“It was so obvious that the scientific literature had so much data about how dangerous it was, and all you hear from these industry places was, ‘no, it’s safe, it’s one of the best studied ones in the country, no regulatory agency has banned it, and on and on,” Evslin says.

“I began to babble about it to my wife, and she said, ‘stop talking about it and write a book’.”

So, he did, published in July 2021: “Breakfast at Monsanto’s: Is Roundup in Our Food Making Us Fatter, Sicker, and Sadder?”

While conducting research for his book, Evslin said, he came across what he said was convincing scientific evidence that glyphosate was pervasive in our food supply and was causing damaging health effects.

Glyphosate-Based Herbicides Changed Seed Science

If chlorpyrifos proved a moral victory for Hawai‘i advocates hoping to limit chemical exposure that can cause developmental delay in children, the presence of glyphosate in food posed a greater challenge.

In plant and crop genetics, one of the most profound changes in agriculture has been to genetically alter seeds so they become resistant to toxic chemicals in glyphosates. That is the primary ingredient used in Roundup, which is produced by Monsanto and has become the world’s most heavily used herbicide in history.

By using seeds that are resistant to glyphosate, farmers can spray their fields with the pesticide, killing everything but the intended crops, and saving millions of dollars on weed control.

After that discovery, use of Roundup and related glyphosate-based pesticides spread like, well, weeds.

“We in the United States use 30-40% of the glyphosate in the world, and we have much less restrictive guidelines” on it, Evslin says. So, everything from soybeans to corn to canola to wheat – many of the ingredients used in our highly processed foods – are often sprayed with glyphosate herbicides and leave traces in the resulting food products that we consume.

Tests, meanwhile, have shown that 80-90% of Americans have glyphosate in their bodies, which dissipates over time but can also be replenished if a steady diet of food and water contain the chemical. And pesticide opponents say they do.

After examining hundreds of scientific studies on glyphosate and glyphosate formulas, Evslin says it became clear to him that there was powerful evidence suggesting links to cancer and other detrimental health effects.

Glyphosate’s Role as an Antibiotic

Amid piles of studies, Evslin thinks he’s found the regulatory Achilles heel for glyphosate.

“It’s definitely an antibiotic,” Evslin says, “And it affects the microbiome – the bacterial content of our intestines and our skin and our respiratory tract. The vital role that it’s playing is only beginning to be fully understood.

“We have more bacteria cells in us than we have human cells. They are an unbelievably integral part of everything – how we think, how our immune system works, how we digest foods.”

Studies, he says, are showing links to obesity, inflammation, DNA changes and liver disease, among other disorders.

But regulatory agencies don’t consider chemicals’ effects on the microbiome, he says.

“What I’ve been trying to do with that is say, yes, I understand,” he says. “But we do regulate antibiotics in food and it’s an antibiotic, and we need to accept that fact. It seems to me it’s an Achilles heel, because it is an antibiotic, we regulate antibiotics, and that should be a short way to get it out of our food.”

Prospects for Section 453

What are the chances that Section 453 of the appropriations bill will be approved?

Rather likely, it turns out. Few Republicans have gone against the party line in any recent votes.

Hawai‘i congress member Tokuda stood firm in a statement ahead of the vote: “Hiding dangerous information on pesticides endangers everyone but especially workers, pregnant women, keiki, and vulnerable communities. It is another win for corporate interests and their priorities and yet another reckless, shameful, and immoral effort by Republicans. No corporation should be above the law, especially when lives are at risk.”

The state’s other representative, Ed Case, also opposed the bill. In a letter to Evslin, he wrote that section 453 and other parts of the bill “prohibit the Environmental Protection Agency from enforcing environmental and public health regulations related to clean water, clean air and hazardous waste and pesticide laws.”

He said he also opposed a 23% cut to the EPA’s budget, “which severely impacts its capabilities to protect human health and the environment.”

Says Evslin: “In terms of what will happen with the bill, my guess is that the House will pass it, and there may be more of a fight in the Senate if it crosses over. The provision is so buried, though, that I don’t think it will get defeated unless there is a dramatic increase in public awareness.”

Either way, after the vote, Evslin will glance out at the tropical land where he once considered gardening, and then he’ll turn his attention back to the latest medical studies examining health effects from long-term exposure to pesticides.

Language of Section 453 of the House Appropriations Bill

SEC. 453. None of the funds made available by this or any other Act may be used to issue or adopt any guidance or any policy, take any regulatory action, or approve any labeling or change to such labeling that is inconsistent with or in any respect different from the conclusion of— (a) a human health assessment performed pursuant to the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (7 U.S.C. 136 et seq.); or (b) a carcinogenicity classification for a pesticide.