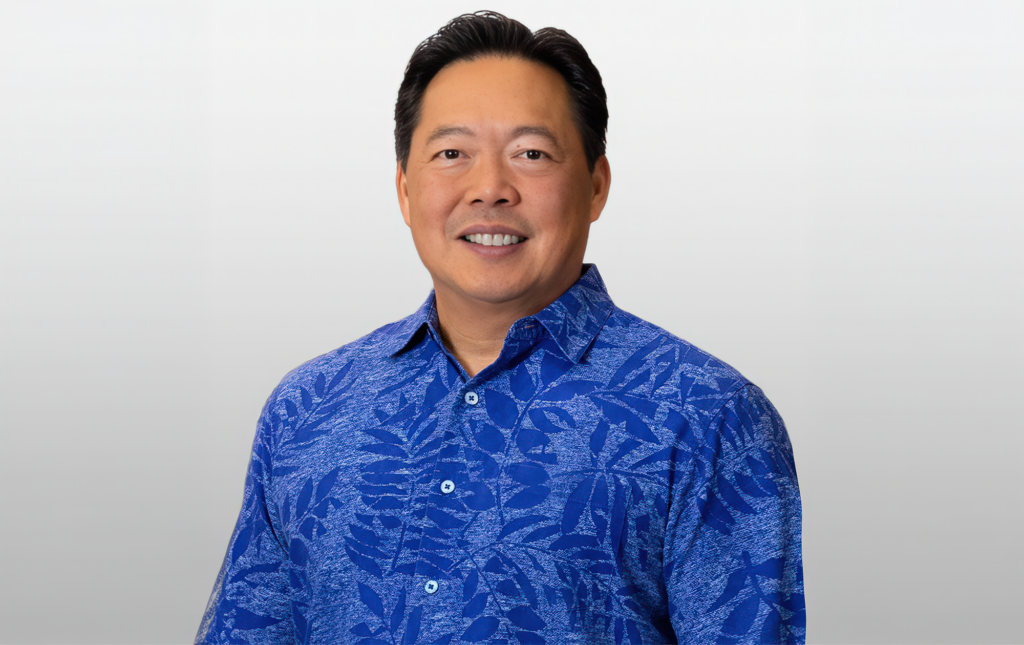

NFL Head Coach Dan Quinn Describes His Leadership Journey

NFL players ranked the Washington Commanders leader as the best head coach in the league

Dan Quinn has enjoyed remarkable success and suffered heartbreaking defeats during 23 years as an NFL coach.

The part-time Hawai‘i resident is now starting his second season as head coach of the Washington Commanders after an impressive first season there: His team won 14 games in 2024 following a 4-13 finish the year before.

The NFL Players Association surveys players each year and its latest report card names Quinn the highest-ranked head coach in the league based on player feedback. He received a perfect score on efficiency – how effectively he uses his players’ time – and the top score for receptiveness to feedback.

I interviewed Quinn to learn how he leads, why he changed part of his coaching style four years ago, how being vulnerable can be a virtue and much more. Here is a condensed version of our conversation.

In the players union’s annual survey, your players said you are very receptive to their suggestions. How do you effectively listen and act on what you hear?

You have to provide spaces for them to communicate with you. I’ve been in the NFL since 2001, and I’ve learned as much from players as I have from other coaches.

What are you learning from them?

All of it, including a lot of tactics, because what may work really well for one person may not work as well for the next. You learn something different from each. [A player suggests something, and I] might say, “Let’s give that a shot. I think that could work.” That’s part of listening, as a leader, to make sure you say, “That’s a good thought.” It may work this week, or maybe we’ll keep working that for a while and try it a few weeks down the road. But having the space to communicate with players is important.

That sounds like you’re not always following what they say.

Definitely not. And I don’t think they would want that either. [There’s] not a lot of discussion during the game – then it’s about the execution. But leading up to that is for exploring and being curious about other ideas. But on game day, that’s not the time to try something for the first time.

How do you ensure you’re listening to every key person, not just the extroverts and loudest voices?

Part of listening has to come from the assistant coaches. I know I’ve done a good job when I hear something coming back from a player that I said only to the assistant coaches in a meeting. I think to myself, “That coach did a good job of passing the message of what we want to do.”

Another part of listening is getting to know the man before the ballplayer. Maybe who they’re playing for: “It’s for money.” “It’s for my child.” “I love competing.” If you can find out the why and you know the man, it makes a big difference, because then you know what they’re fighting for. It takes a while. It doesn’t happen in one week. Some players take longer to get to know.

When you came to Washington, you added some players who had played for you in the past, on other teams. Why was that important?

Yeah, sometimes [they’re] people who can see around the corners or be in the rooms that you’re not. They understand [and explain to the other players], “Here’s what Dan’s trying to say,” or “Here’s what he means,” because then it’s not just one voice of leadership, it’s multiple.

Early in my career, I thought leadership was me. How do I lead them? As I got further along, I realized it’s really as much about developing the leadership in others and bringing it out of them. Now, leadership is about them, what they stand for. That’s been a big shift for me.

I have to be the voice of direction, and at times be the hammer. I also know I have to develop the next group of leaders.

Using players’ time effectively is key for any NFL coach, and the players survey suggests you do that especially well. What are your guiding thoughts?

Players make a lot of sacrifices. Their families make a lot of sacrifices too. So I want to make sure that on their breaks, they get away from football and find their own balance, and that the times when they are away from their families are productive and meaningful. The times we’re together are really intense – all their focus, all their energy and intensity.

We have families come for Saturday morning walk-through practices before Sunday home games. It’s a way for the families of players and coaches to connect. A food truck or ice cream truck comes after practice. There’s nothing like it: 100 kids on the field together, yelling and full of energy, and kind of growing up together.

When you assess players for a football team, their physical characteristics are most important. What else do you value?

First and foremost, what’s behind the rib cage? Why is playing here, competing for us, so important? Is this person really committed to doing it?

The other thing I want to find out is what kind of resilience they have. Most people, whether it’s in football or in life, they’re going to go through things, so they better have some resiliency. So finding out what they’ve been doing, where they’re at, how they’ve dealt with that – I think that’s a pretty good indicator of how they’re going to respond when it gets hard. Because let’s face it, whether it’s in sports or business or in life, there’s going to be hard moments, and how you’re going to respond and react and behave in those moments tells a lot about the type of teammate you are and [whether you] can be counted on.

But even resilient people can get discouraged by hard times. How do you help pull people out of that?

It’s customized per person. The youngest players may need to hear, “You can do it. You belong in this league.” Assuring them you have their back, you have a vision for what they can do, even if they can’t see it. Tell them, “Here are the things you need to keep working on.”

That’s different from a player in the middle of their football career. For that player, it may be, “This time we do this and this, these two things.” And for the older player, maybe this is their last go of it. “Take care of your body because you’ve been playing for a long time.”

It’s being able to respond to what the individual needs at that time. But in the end, the connection between everyone is really what pulls you out, because you’re not going at it alone. Not everybody has the same energy every day: “If you pull me up today, I’ll feed you tomorrow.”

That requires trust in each other. How do you build that trust?

It takes a while and it does require honesty. At times, you must have hard conversations – you don’t have to be a jerk to do it – whether it’s performance-based behavior or whatever. Pro ballplayers have been BSed at some point – you know during recruiting [by colleges], etc, so we need to shoot it straight. “This is what we expect. This is what we need.” And more times than not, I felt they responded best.

If they aren’t aware that they’re not hitting their marks, that’s a real problem. So having the self-awareness, knowing where they’re at and then we can say, “These are the things I think we need to do over the next couple of weeks to fix those things. If you can do those, then I think it’s not going to stay at that space.”

After you were fired as head coach of the Atlanta Falcons midseason in 2020, you did something out of the ordinary: You asked a TV sideline reporter to collect confidential feedback from 30 to 40 people who had worked with you – some were supporters, but others were people you had cut or fired. When you got the anonymous feedback, you focused on the negatives, not the positives. What did you learn and how did you correct those shortcomings?

I followed a format similar to a business 360 review. In Atlanta, I worked for Arthur Blank [owner of the Falcons and co-founder of Home Depot], so I was familiar with what a 360 was in business. I wanted to do it from a football perspective. Questions like, “What went well?” “What could have been done differently?” But it wasn’t just people at the organization; there’s some players from a previous team, coaching staff, front office. I wanted to find out if I had any blind spots, and the purpose behind it was my next lap. In the next shot, I wasn’t going to repeat the same mistakes.

I got the feedback while I was in Hawai‘i, and, wow, it was insightful. I went past the good things quickly down to the bottom. It didn’t matter to me who it came from. In fact, I didn’t want any names attached. Some people called me – “Do you know this is happening?” and [I’d respond,] “Yeah, I want you to answer.”

It was helpful, because going into my next stop, I was able to apply some of those things that I specifically wanted to do better. At the time I was let go, I thought it was the worst thing that could happen professionally – early in a season [after an 0-5 start]. Looking back on it now, it was the best thing, because I don’t know if I would have had the same reflection time had I been let go in January and then started somewhere else soon after. That space, on vacation, although uncomfortable, gave me the time to find out what I could do.

Great leaders often say you don’t learn from success so much as failure.

Yeah, I didn’t want to repeat anything that potentially I could change. But you don’t have to wait until you’re let go or wait for the numbers to fall. You just have to be reflective enough. Even when it’s going good, you can ask: How can it go better?

What was the main thing you learned from that 360?

Like a lot of business leaders, I like solving problems, so I was probably spreading myself too thin. “How can I get the most out of this person?” “I can help with that.” “That’s interesting, I can help with that too.” Before long, I was working harder than I ever had but having fewer results.

So it was important to delegate. [Now it’s,] “This is the project we need to get done. See me on Thursday at 3 o’clock.” That way my focus could be on the really important decisions that we have each week, game plan-wise, team-wise. I really took that feedback to heart. My previous way of doing things came from a good place – of wanting to help – but it wasn’t the right thing to do. Now I want to make sure I keep the main thing at the very front of the line.

Today, the follow-through has become so much more important to me than just the idea. Is it going to be applied? If we have done all the preparation and made the right call, then even if it doesn’t go your way, I can live with the results.

Who are your leadership role models, inside and outside of football?

Mostly coaches that I worked with. My first job in the NFL was for the 49ers, and Steve Mariucci was the head coach. Another was Nick Saban [when he was head coach of the Miami Dolphins], and after that, the Seattle Seahawks with Pete Carroll. Those three guys, all of them were different, but, man, watching them build an organization, getting everyone on the same page – in college, you didn’t have that as much.

By going to those NFL teams, when you walked into the building, everybody knew this is how you do things. And with those three, Mariucci, Saban and Carroll, you felt that players knew it, staff knew it, it really clicked.

Outside football, the NBA has done such a great job of developing players. So I enjoy visiting with NBA coaches, although it’s not schematically the same, there’s a lot you can learn about taking a player from point A to point B and then taking them from being very good to becoming great.

You’re a very open person. What role does vulnerability play in building trust?

Great topic. There has to be vulnerable spots, so others know, “I can count on this person.” They’ve been through an experience that they’ve shared [with staff and players] on why it went well or why it hasn’t.

Being able to help somebody become their very best is what I love about coaching most. First see if we can help the coaches elevate, that helps the players. You can’t ask the players to improve and not ask the coaches to improve.

It takes vulnerability to say, “I’ve screwed this up with a player before. I’m not going to make those same mistakes.” Those things make a big impact. Our time together is short, so make sure you use the time well. If you do that right, it multiplies in the locker room. Then they can start trusting and being vulnerable with the next group of players.

For the people who are not super football fans, please explain how many people you lead?

You have 53 players on the team, 16 on the taxi squad [reserve players], 20 to 25 coaches. There are 90 that come to training camp; you cut the roster down to 53, then you can add practice squad players.

It’s always changing. No team is the same from year to year. There’s a draft [by all NFL teams of college players] and injuries. That’s why I think having a culture and a standard that you must meet as a teammate, as a coach, is really important.

You plan for everything, but things can go wrong. How do you know when it’s time to change the plan?

Early in my career, I thought, “This is how it’s going to go.” Now I’ve become much more accustomed to saying, “Adversity is coming. Things are going to have to change.” So we practice a lot of the situations – being behind, being ahead – so we can react to those each week. Every practice, from training camp through the regular season, will include some of those situations: 8 seconds left, 15 seconds; with a timeout, with no timeout; you’re down two scores, you’re down by one; you’re ahead by one, you’re ahead two. If we do those over and over, those situations in the game will feel normal for everybody. Games are super tight and intense, but the more we’ve done them in practice, we have something to go back on.

The situations don’t come up every week: Sometimes we practice something in September and we don’t do it again until November, but we have done it. I want the players to really feel ready for those spots.

Sometimes on a dry day, I’ll make the football wet – spray it, dunk it in a bucket – so we’re able to play in the rain. Some practices we were under 30 degrees, and the players were not happy, but that’s what January football is like in Washington, D.C.

Last question: How do you handle egos? Your people are getting paid millions of dollars.

It’s not just players; it’s coaches, ownership, all of it. I think it still comes back to the relationships. And if you have a good relationship, [you can say], “Hey, what’s going on? You’re not yourself right now.” And if you’ve built that relationship over time, “I’ve got you.” If you don’t have that, it’s much more difficult.

I’m much more one to go directly at it to say, “Hey man, that doesn’t sound like you. Are you pressing? Are you over-trying here? What’s the cause of this because you’re a great teammate and that doesn’t sound like you.” Those are things that can kill a team.

Pride, performing well, being excellent – love that. But if I feel like it gets in the way of the team, that’s different. So I allow some space. But if I feel like you’re going over the line into it’s more about me, I say, “Hey man, come over here and stand next to me for a while.”

We’re not going to allow one person’s ego to disrupt the team, because we’re playing for something much bigger than ourselves. Once it crosses the line into “It’s more about me,” then [I’ll say,] “If you’re not going to get back on board with the program, then next week you’re going to sit over there.”