Haleakalā National Park’s Nick Clemons Talks About His ‘Dream Job’

Working At A Park That Goes from Sea Level To 10,023 Feet

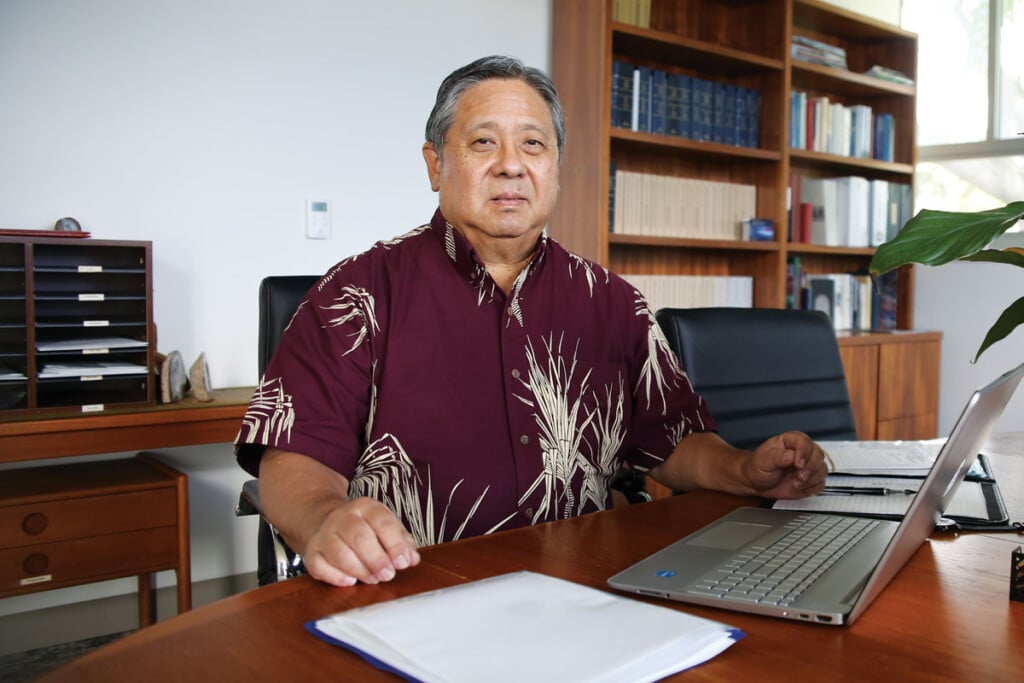

Name: Nick Clemons

Job: Chief of Interpretation, Education and Volunteers, and Public Information Officer at Haleakalā National Park

Haleakalā National Park’s world-famous views, hikes and 25,000 acres of wilderness draw as many as a million visitors a year, and the park rangers who work there face all kinds of challenging situations, including extreme weather, lost or dehydrated hikers, missing children and big crowds, especially at sunrise.

For Nick Clemons, the park’s chief of interpretation, education and volunteers, it’s a dream job. “I have just been blown away by everything this park has to offer, from the summit down to the sea in Kīpahulu,” he says.

BEGINNINGS

Clemons has worked for the National Park Service for 17 years – ever since college graduation – and even served as a volunteer before then.

He was with the Upward Bound Program – a federal program that helps students from low-income families to finish high school and college by connecting them with nonprofits – when he met park rangers who worked in resource management. They seemed to enjoy their jobs, he says, and that helped inspire him to work for the park service straight out of college.

MANY STOPS

Before coming to Maui, he worked at five National Park Service sites on the East Coast:

- Assateague Island National Seashore, a barrier island off Maryland and Virginia that is known for its wild horses.

- Three sites in Philadelphia: Independence National Historical Park, home to Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell; the nearby former home of writer Edgar Allan Poe; and the national memorial for Thaddeus Kosciuszko, a hero in both his native Poland and in the American Revolutionary War.

- Fire Island National Seashore, a barrier island off the south shore of Long Island, New York.

CURRENT JOB

Resource management and planning led Clemons to the park service but now his role is mostly to support his fellow rangers as they lead hikes, staff the visitor centers, do outreach work with volunteers and perform other services.

After a temporary assignment at Haleakalā National Park in the summer of 2024, he was offered a permanent job there.

“A typical day for me, I come in and typically check in with the staff to see how their morning is shaping out, what their expectations for the day are and just to let them know I’m here,” Clemons explains. “I answer emails and I look at anything that is pressing for our work plan that really needs to get done and to make sure that they have the support they need.”

BIG CHALLENGES

With a summit that is almost 2 miles high, Haleakalā’s weather can vary wildly – from days that are sunny and mild to those with 50 mph winds and even stronger gusts, snowfall and freezing temperatures. The sometimes wintry scenes can surprise tourists who expect tropical weather, and fast-changing conditions, altitude sickness and dehydration can disorient and confuse even the most experienced hikers, Clemons says.

“Every visitor is different in their expectations, and we do our best to meet those expectations while also following our policies and guidelines to protect both the visitor and the resource,” he says.

“Emergencies can range from an injured hiker on a trail or a missing child or adult, whether at the summit or the Kīpahulu district.”

BEST PART OF THE JOB

Clemons loves seeing visitors enjoying all that Haleakalā offers, especially the spectacular views.

“The sunrise is always what comes to mind, but the sunset as well and once the sun is fully set, the night sky is amazing. A lot of people have never seen the Milky Way before, and to see it on Haleakalā is so special. You feel so close to the sky,” he says. “I’ve seen tears streaming down their faces at the sheer beauty of the sight.”

HAWAIIAN CULTURE

Haleakalā is a sacred place for Native Hawaiians and Clemons says the park service tries to reflect that in its activities. Guides discuss the place’s history, and a morning prayer welcomes the sun every morning before it rises.

“Our education specialist is also our Native Hawaiian liaison. All projects we have within the park go through an interdisciplinary review team, and we consult with local Native members to make sure the Hawaiian perspective and culture are incorporated into our projects,” Clemons says.

“They have a chance to review and comment on it before ground is broken on whatever project we’re working on, so their perspective is never neglected.”

LOVES HIS JOB

Clemons says everyone loves America’s national parks – “the crown jewels of public land.” And now Haleakalā has captured his heart.

“Who can say that they work in a park that goes from sea level to 10,023 feet?” he exclaims.