Building Bridges to China

EB-5 INVESTMENTS

Hits and Misses for a Federal Program

Maybe the best-known vehicle for foreign investment in Hawaii is the EB-5 program. Run through the U.S. Center for Immigration Services, EB-5 gives wealthy foreigners (and their immediate families) green cards in exchange for investing money and creating jobs in the U.S. The price of admission is $1 million, although in rural or economically disadvantaged areas – which includes most of Hawaii – investors only need $500,000.

There are two ways foreigners can participate. One is individually: use your $500,000 to start a company, create (or save) 10 jobs over two years and manage the business yourself. But, like any startup – let alone one owned and managed by a new immigrant – this kind of investment is risky. If it fails, the investor loses both his money and his provisional green card. The other approach, investing through a USCIS-approved “regional center,” is much more popular.

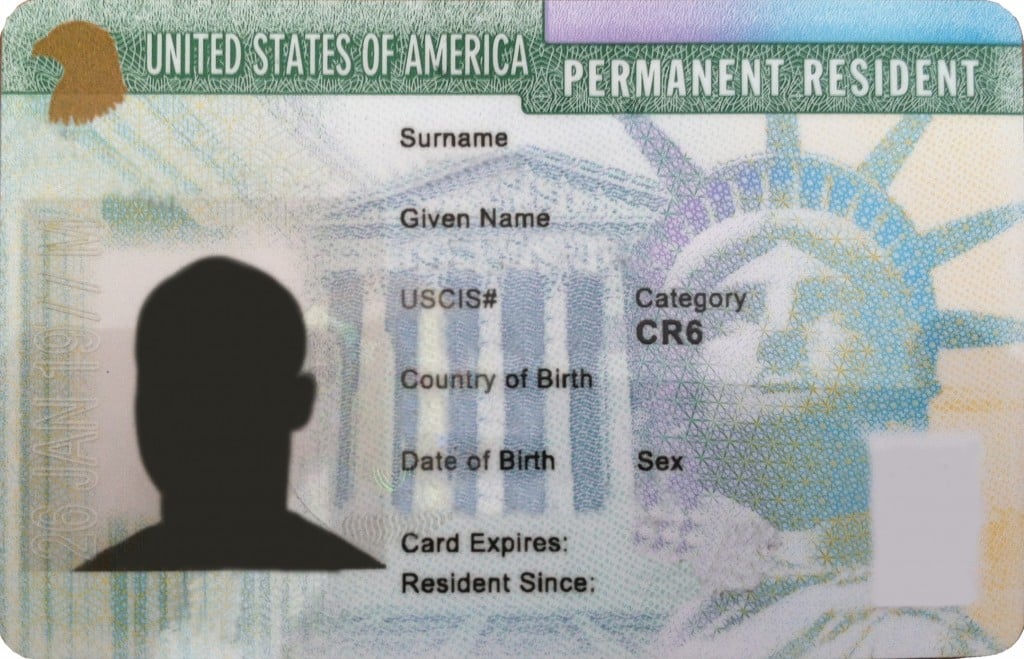

For foreign investors, the main lure of the EO-5 program is a “Green Card,” the nickname for the card that proves you are a legal permanent resident of the U.S. Invest at least $500,000 and create or save 10 jobs under EB-5, and the card may be yours.

At its heart, the regional center is a brilliant concept. Basically, after a company is approved by USCIS to create a regional center, it finds foreign investors, identifies an appropriate project (big enough that all the investors qualify for EB-5), then structures the deal as a limited partnership, with the regional center as the managing partner and filing the necessary reports with USCIS. In this scenario, everybody wins. The investors (and their immediate families) get their green cards and (hopefully) an attractive return on their investment; the region gets jobs and economic development; and the company that manages the regional center takes a cut of the profits. For the glut of wealthy Chinese nationals eager to gain legal status, send their children to U.S. schools and get some of their assets out of China, EB-5 seems like the ideal vehicle. In practice, though, the program isn’t as straightforward as that, especially in Hawaii.

Problems From the Start

Hawaii’s history with the EB-5 program goes back to at least 1995, when DBEDT created the Hawaii Regional Center. Betty Brow, executive VP of Bank of Hawaii’s International Banking Division, estimates that “between 2000 and 2011, Hawaii had about $100 million in EB-5 investment,” much of it through one project, Sopogy.

But EB-5 has had problems almost from the beginning. Nationally, it has been plagued by an inefficient bureaucracy and by allegations of corruption and mismanagement at some regional centers. Most recently, Gulf Coast Funds Management, a regional center affiliated with Anthony Rodham, Hilary Clinton’s brother, has been accused of using improper influence and receiving preferential treatment. A 2005 GAO audit found widespread inefficiency and mismanagement, shutting down nearly 900 EB-5 cases. In fact, the current incarnation of EB-5 is technically a pilot program. This uncertainty at the federal level complicates the long-term viability of regional centers.

Locally, the issue has been mostly a lack of activity or oversight. As Alan Ma points out, USCIS actually suspended the state’s program in 2007. “The Hawaii Regional Center, which was managed by DBEDT then, lacked what it called ‘oversight management,’ ” Ma says. “The truth was that DBEDT did not submit the required statistical information on how the Regional Center was doing. CIS wasn’t pleased when the state didn’t know what was going on with the regional center.”

“So they (DBEDT) hired an independent contractor called CanAm Enterprises,” Epstein says. “CanAm was contracted to run the center under a five-year agreement and take over the responsibilities that DBEDT had and was unable to perform.” Ma actually served as a consultant for CanAm. And yet, both he and Epstein are dubious about its performance. They say that, although the Hawaii Regional Center has three prospective projects – the Honolulu International Airport consolidated rental car parking facility, UH West Oahu student housing and Sopogy’s Kalaeloa solar project – none have yet been fully approved by USCIS. They contrast this with the company’s performance in other parts of the country.

“In the last five years,” Epstein says. “CanAm had four other regional centers for which they raised $1.3 billion of investment money. They raised zero for Hawaii.” Indeed, the perception among many in the local EB-5 community is that DBEDT promotes CanAm, but CanAm siphons off potential Hawaii investors to its more successful regional centers on the mainland. Ma and Epstein worry DBEDT will cancel the program. They may have a point. CanAm’s management contract actually ended in March; since then, the company has been operating the regional center under a temporary extension. Meanwhile, Dennis Ling, the administrator for strategic marketing at DBEDT, says the state hasn’t made a decision yet on whether to renew the contract or continue the program.

CanAm, of course, has a different perspective on the Hawaii Regional Center. Although the company declined to be interviewed for this story, in an email, executive VP Christine Chen says all three of the regional center’s projects are fully subscribed – that is, they’ve found investors and the investors’ money is in escrow. According to CanAm, the delay in starting construction on these projects is because of USCIS’s slow approval process. That’s a chronic complaint about EB-5.

By law, USCIS is required to approve the regional center, approve the investors and approve the project. Each of these processes generates reams of paperwork and can be remarkably slow. For example, the agency can take years approving the investors, who have to demonstrate to the agency that their investment funds are all legally obtained. Similarly, USCIS’s analysis of projects to prove they will generate the appropriate number of jobs can be time consuming and complex.

Despite these snags, CanAm says, it has made quiet progress on its projects. According to Chen, “All the investors in two of the projects have been approved. The third project, for the Honolulu Airport, is pending adjudication at USCIS, but all the investor petitions have been submitted and the funds deposited in escrow.” In other words, CanAm hasn’t had any problem finding investors. They also discount the suggestion they siphon potential Hawaii investors to other regional centers, noting:

“CanAm maintains a waiting list of pre-screened investors who wish to subscribe to projects in the various regional centers we operate. Some investors prefer certain types of projects, others prefer certain regions.” Some specifically prefer Hawaii, Chen says.

Nonetheless, all three Hawaii Regional Center projects remain in limbo.

Two Are Inactive

Fortunately, CanAm doesn’t operate the only regional center in Hawaii. In fact, there are four of them; although, like many regional centers around the country, two appear moribund. Neither the Golden Pacific Ventures regional center, which is attempting to sell investors shares in coffee farms on Hawaii Island, nor Live in America Financial Services, an idle regional center recently bought by Lexington Realty Trust, the former owner of the old Macy’s building downtown, have any active projects.

On the other hand, the Hawaiian Islands Regional Center, which is developing a 100-bed skilled nursing facility on Hawaii Island and a 175-bed skilled nursing facility on Maui, may be a model for how to use EB-5 to bring Chinese investment to the state.

“We’ve found a niche,” says David Wilson, who, along with partners Ben Meeker and Andre Hurst, founded the Hawaiian Islands Regional Center in 2008. Indeed, skilled nursing facilities seem ideal for EB-5. They’re expensive to build, which means they can absorb a lot of foreign investment. They generate a lot of employment – between them, the Maui and Hilo facilities are projected to create 450 jobs, many of them highly paid. And maybe most important, they create a reliable revenue stream. That makes skilled nursing facilities easy to explain, both to Chinese investors and USCIS analysts.

But Wilson points out that the success of the Hawaiian Islands Regional Center isn’t just the result of the type of project it has chosen. It also approaches the EB-5 program differently. While other regional centers often take an equity position in their investments, Wilson and his partners function more like a bank, acting as lenders rather than owners of their projects. For both current Hawaii projects, the Hawaiian Islands Regional Center is working with Regency Pacific, which operates more than 50 skilled nursing and rehabilitation facilities around the country, including two on Kauai and one in Kona.

Wilson points out that the Hawaiian Islands Regional Center also sequences its deals differently than most regional centers. For example, they seek USCIS approval for their projects before they look for subscribers.

“Our projects are already approved,” Wilson says. “In other words, we’ve sent in all our documents, all those documents have been vetted, and we’ve been back and forth on requests for evidence to make sure every ‘i’ has been dotted and every ‘t’ has been crossed. My understanding is that CanAm has filled out the subscriptions on their projects, but those projects have not been approved, so they haven’t really been funded.”

But, just as in the legal world, the most important attribute of a regional center that wants to attract Chinese investment is probably the ability to build relationships. That means being face to face with your potential investors. So, while CanAm says it markets its program “through a select group of authorized sales agents that are registered and/or licensed in China,” the Hawaiian Islands Regional Center is actually in the country. “Our company, as far as I know, is the only regional center that’s also a Chinese corporation,” Wilson says. “To make a long story short, we’re where the money is at.”